1913年 , 維也納如何改變了世界

一戰(zhàn)前名符其實的帝都,也是無數(shù)天才人物集聚的場所。相比之下,巴黎、倫敦、紐約之流都弱爆了。數(shù)數(shù)看歷史中必然留名的,希特勒、托洛茨基、鐵托、弗洛伊德、斯大林……此外,克林姆特當然早已功成名就,而穆齊爾在維也納技術大學管理圖書,勛伯格在音樂學院教和聲;還有維也納大學里的師生們:米塞斯當時還是一名編外講師,薛定諤剛在第二物理研究所嶄露頭角,維特根斯坦成了帝國數(shù)一數(shù)二的富豪,莫雷諾開始最早的心理劇實驗,阿德勒與弗洛伊德趨向決裂,而哈耶克與波普爾則是文法學校內的小屁孩。

1913年的維也納如何改變了世界

BBC 2013年4月20日

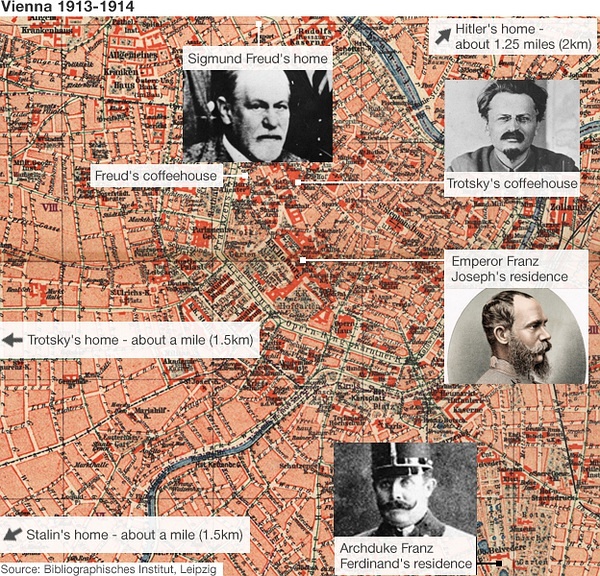

一個世紀之前,希特勒、托洛茨基、鐵托、弗洛伊德和斯大林曾經同時在奧地利首都維也納活動。

《真理報》的一名異見編輯、左翼領袖托洛茨基曾經寫道,他于1913年1月與持假護照的斯大林在維也納會面。

斯大林和托洛茨基是1913年生活在維也納中心的兩位重要人物之一,這些人命中注定塑造了(或者說粉碎了)20世紀大部分的世界歷史。

這些重要人物當時的境遇各有不同。斯大林和托洛茨基是在逃的革命家,而弗洛伊德已經非常有名。

知名精神分析學家弗洛伊德當時已經在維也納執(zhí)業(yè)。

當時尚年輕的前南斯拉夫領導人鐵托在維也納以南維也納新城的戴姆勒車廠工作,尋求就業(yè)、金錢和美好的時光。

與此同時,希特勒正在維也納美術學院學習。當年24歲的希特勒來自奧地利西北部,為追求自己的藝術夢想居住在多瑙河附近Meldermannstrasse的廉價旅館里。

1913年的維也納是奧匈帝國首都。這個帝國下轄15個國家,人口超過5000萬人。

1848年革命后繼位的奧匈帝國皇帝弗蘭茨·約瑟夫居住在霍夫堡皇宮。

皇儲斐迪南大公居住在附近的美景宮,熱切等待繼承皇位。斐迪南大公1914年被暗殺,引發(fā)第一次世界大戰(zhàn)。

奧地利唯一英文月刊《維也納評論》主編麥克納米在維也納居住了17年。她說,1913年的維也納雖然不能說是一個“大熔爐”,但確實是自身特有的一種文化“濃湯”,吸引奧匈帝國各地的有野心人士。

麥克納米介紹:“當時維也納200萬人口中,不到一半在本地出生,約1/4來自現(xiàn)屬捷克的波希米亞和摩拉維亞地區(qū),所以很多維也納居民除了講德語也講捷克語”。

“奧匈帝國的居民講數(shù)十種語言,軍隊官員除了德語之外,需要用其它11種語言下達命令,每一種語言都有國歌的官方翻譯”,她說。

這種混雜的局勢創(chuàng)造了一種獨特的文化現(xiàn)象——維也納咖啡館。維也納咖啡館的起源相傳是1683年奧斯曼土耳其軍隊攻城失敗后留下的裝滿咖啡豆的麻袋。

《1913:尋找大戰(zhàn)前的世界》一書作者、英國皇家國際關系研究所高級研究員查爾斯·埃默森說:“咖啡文化和在咖啡館舉行辯論的概念是當年和今天的維也納文化”。

埃默森解釋:“維也納的知識界其實很小,大家彼此都認識,這為跨文化的交流提供了條件,也對政治異見人士和在逃人士有利”。

他還說:“對在逃的異見人士來說,維也納是歐洲最好的藏身之處,因為可以結識很多有意思的人”。

弗洛伊德最喜歡的Landtmann咖啡館仍然佇立在維也納內城區(qū)。

托洛茨基和希特勒經常光顧的Central咖啡館只有幾分鐘的步行距離,那里的蛋糕、報紙、象棋,當然最重要的是那里發(fā)生的討論點燃食客們的激情。

《維也納評論》主編麥克納米說,讓這些咖啡館變得重要的部分原因是,大家都去,所以各方興趣匯集起來,西方思維中的嚴格界限在這里變得很靈活。

她表示,除此之外,猶太人知識界、新工業(yè)階層在1867年獲得奧匈帝國皇帝弗蘭茨·約瑟夫授予完整公民權、可以上大學之后,1913年逐步崛起。

盡管維也納當時、現(xiàn)在仍然是音樂、豪華舞會、華爾茲的代名詞,它也有黑暗慘淡的一面——當時很多維也納居民生活在貧民窟,1913年有近1500人自殺。

盡管沒有人知曉,希特勒當年是否曾經偶遇托洛茨基、鐵托或者斯大林,但是勞倫斯·馬克斯2007年創(chuàng)作的廣播劇《弗洛伊德現(xiàn)在可以見你,希特勒》等作品想象了這種場景。

第二年(1914年)點燃的戰(zhàn)爭之火摧毀了維也納的知識界。

奧匈帝國于1918年分崩離析,推動了希特勒、斯大林、托洛茨基和鐵托開始永遠改變世界的歷史。

1913: When Hitler, Trotsky, Tito, Freud and Stalin all lived in the same place

By Andy Walker Today programme, BBC Radio 4

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21859771

A century ago, one section of Vienna played host to Adolf Hitler, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Tito, Sigmund Freud and Joseph Stalin.

In January 1913, a man whose passport bore the name Stavros Papadopoulos disembarked from the Krakow train at Vienna's North Terminal station.

Of dark complexion, he sported a large peasant's moustache and carried a very basic wooden suitcase.

"I was sitting at the table," wrote the man he had come to meet, years later, "when the door opened with a knock and an unknown man entered.

"He was short... thin... his greyish-brown skin covered in pockmarks... I saw nothing in his eyes that resembled friendliness."

The writer of these lines was a dissident Russian intellectual, the editor of a radical newspaper called Pravda (Truth). His name was Leon Trotsky.

The man he described was not, in fact, Papadopoulos.

He had been born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, was known to his friends as Koba and is now remembered as Joseph Stalin.

Trotsky and Stalin were just two of a number of men who lived in central Vienna in 1913 and whose lives were destined to mould, indeed to shatter, much of the 20th century.

It was a disparate group. The two revolutionaries, Stalin and Trotsky, were on the run. Sigmund Freud was already well established.

The psychoanalyst, exalted by followers as the man who opened up the secrets of the mind, lived and practised on the city's Berggasse.

The young Josip Broz, later to find fame as Yugoslavia's leader Marshal Tito, worked at the Daimler automobile factory in Wiener Neustadt, a town south of Vienna, and sought employment, money and good times.

Then there was the 24-year-old from the north-west of Austria whose dreams of studying painting at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts had been twice dashed and who now lodged in a doss-house in Meldermannstrasse near the Danube, one Adolf Hitler.

In his majestic evocation of the city at the time, Thunder at Twilight, Frederic Morton imagines Hitler haranguing his fellow lodgers "on morality, racial purity, the German mission and Slav treachery, on Jews, Jesuits, and Freemasons".

"His forelock would toss, his [paint]-stained hands shred the air, his voice rise to an operatic pitch. Then, just as suddenly as he had started, he would stop. He would gather his things together with an imperious clatter, [and] stalk off to his cubicle."

Presiding over all, in the city's rambling Hofburg Palace was the aged Emperor Franz Joseph, who had reigned since the great year of revolutions, 1848.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, his designated successor, resided at the nearby Belvedere Palace, eagerly awaiting the throne. His assassination the following year would spark World War I.

Vienna in 1913 was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which consisted of 15 nations and well over 50 million inhabitants.

"While not exactly a melting pot, Vienna was its own kind of cultural soup, attracting the ambitious from across the empire," says Dardis McNamee, editor-in-chief of the Vienna Review, Austria's only English-language monthly, who has lived in the city for 17 years.

"Less than half of the city's two million residents were native born and about a quarter came from Bohemia (now the western Czech Republic) and Moravia (now the eastern Czech Republic), so that Czech was spoken alongside German in many settings."

The empire's subjects spoke a dozen languages, she explains.

"Officers in the Austro-Hungarian Army had to be able to give commands in 11 languages besides German, each of which had an official translation of the National Hymn."

And this unique melange created its own cultural phenomenon, the Viennese coffee-house. Legend has its genesis in sacks of coffee left by the Ottoman army following the failed Turkish siege of 1683.

"Cafe culture and the notion of debate and discussion in cafes is very much part of Viennese life now and was then," explains Charles Emmerson, author of 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War and a senior research fellow at the foreign policy think-tank Chatham House.

"The Viennese intellectual community was actually quite small and everyone knew each other and... that provided for exchanges across cultural frontiers."

This, he adds, would favour political dissidents and those on the run.

"You didn't have a tremendously powerful central state. It was perhaps a little bit sloppy. If you wanted to find a place to hide out in Europe where you could meet lots of other interesting people then Vienna would be a good place to do it."

Freud's favourite haunt, the Cafe Landtmann, still stands on the Ring, the renowned boulevard which surrounds the city's historic Innere Stadt.

Trotsky and Hitler frequented Cafe Central, just a few minutes' stroll away, where cakes, newspapers, chess and, above all, talk, were the patrons' passions.

"Part of what made the cafes so important was that 'everyone' went," says MacNamee. "So there was a cross-fertilisation across disciplines and interests, in fact boundaries that later became so rigid in western thought were very fluid."

Cafe Central, Vienna Both Trotsky and Hitler sipped coffee under Cafe Central's magnificent arches

Beyond that, she adds, "was the surge of energy from the Jewish intelligentsia, and new industrialist class, made possible following their being granted full citizenship rights by Franz Joseph in 1867, and full access to schools and universities."

And, though this was still a largely male-dominated society, a number of women also made an impact.

Alma Mahler, whose composer husband had died in 1911, was also a composer and became the muse and lover of the artist Oskar Kokoschka and the architect Walter Gropius.

Though the city was, and remains, synonymous with music, lavish balls and the waltz, its dark side was especially bleak. Vast numbers of its citizens lived in slums and 1913 saw nearly 1,500 Viennese take their own lives.

No-one knows if Hitler bumped into Trotsky, or Tito met Stalin. But works like Dr Freud Will See You Now, Mr Hitler - a 2007 radio play by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran - are lively imaginings of such encounters.

The conflagration which erupted the following year destroyed much of Vienna's intellectual life.

The empire imploded in 1918, while propelling Hitler, Stalin, Trotsky and Tito into careers that would mark world history forever.

You can hear more about Vienna's role in shaping the 20th Century on BBC Radio 4's Today programme on 18 April.